Music and movement at the Before I Die wall in downtown Asheville.

Dance

All images © Joe Longobardi. All Rights Reserved.

joelongobardiphotography.com/

joelongobardiphotography.com/books

Music and movement at the Before I Die wall in downtown Asheville.

Dance

All images © Joe Longobardi. All Rights Reserved.

joelongobardiphotography.com/

joelongobardiphotography.com/books

June 19, 2015, downtown Asheville, North Carolina.

As I was grabbing a few candid shots of this family, the father noticed that I was taking his photograph. He immediately grabbed his daughter and posed for this shot. No words were really exchanged except for a “thank you” from me.

Father and child

All images © Joe Longobardi. All Rights Reserved.

joelongobardiphotography.com/

joelongobardiphotography.com/books

From a series of photos I had taken of several couples dancing to the street musicians performing off in the distance. This is almost as close as one may want to get with a 24mm lens before a dancing couple knocks you over.

Dancing on College Street

All images © Joe Longobardi. All Rights Reserved.

This blog part of a series and accompanying introduction to a street photography event that will happen on June 19, 2015 in downtown Asheville, North Carolina. For more information visit Street Photography and the Summer Solstice on Facebook.

The 50mm lens is back!

First, let me start by stating that my lens of choice has currently been the 28mm, and just behind that the 35mm. They allow me to rely on such techniques as scale focusing, also know as zone focusing, at small enough apertures (f-stops) to maintain enough depth of field (also known by the acronym DOF) to keep my subject of interest in sharp focus. This comes in quite handy when shooting the fast pace of a city on the fly! People are constantly on the move, and even though a fast shutter can freeze the action, having a large depth of field is far more forgiving in keeping things in focus, even at slower shutter speeds. This larger DOF is also advantageous when the subject is moving towards or away from you and begins to move outside the area of best focus. Having that greater depth ensures that the moving object retains an acceptable level of focus and sharpness. Plus you can get in close to your subject while still taking in enough of the surrounding environment. There may be more information to compose correctly for the final image, but done just right it can have a very dynamic impact on the final result. Case in point, the following image was shot with a 28mm using scale focusing (zone focusing).

Shot from the hip with 28mm lens

And this was shot using a 35mm lens.

Kids crossing street. 35mm lens.

In both these instances I used a technique known as “shooting from the hip” where once I have my distance calculated via the distance scale on my lens (found on a manual or earlier auto focus lens, many modern digital no longer have aperture rings, so the distances are not marked on the lens), I can gauge how much depth of field I will have as I approach a subject moving towards me at a similar pace. And although I never lifted the viewfinder of the camera to my eye to frame this shot, the image more or less came out as I had anticipated. This of course was achieved through lots and lots of practice! In other words, I know how the lens will frame the content from certain angles such as waist or chest height. Over time, the lens becomes an extension of the body. Another very useful technique when shooting street photography incorporates focusing a lens such as the 28mm at its hyperfocal distance. This often achieves the best balance of sharpness from foreground to background.

But I find the 50mm is still the go to lens for when I need to take in information at such a hurried pace, and can’t move fast enough towards something of interest a distance away. The 28mm used for the first image above allowed me to get very close (about 4 feet away), and I still got a lot of information in the photo while keeping the subjects in focus. The 50mm lens on the other hand requires more “breathing space”, if you will. Not just because it’s longer requiring you to step back, but also as the focal length of any lens increases, images shot with a 50mm at the same f-stop and distance from subject as a shorter lens have less depth of field, and therefore less of the scene in focus. And of course, the longer the lens, the more narrow the field of view (FOV). A wide lens such as the 28mm can take in 300% more of a scene than a 50mm. Even a 35mm takes in approximately 200% more than it’s 50mm cousin.

Once a very popular general lens, over time, the 50mm prime was abandoned by many photographers. This was partly due to the increase in quality of zoom lenses that covered that focal length, but also as wider lenses became more in vogue with photojournalists and the public in general, the 50mm was seen as a very, well…boring lens. When digital cameras became the norm, most inexpensive sensors were smaller cropped versions (APS-C) of a 35mm equivalent, resulting in a narrow field of view similar to a telephoto or portrait lens of approximately 80mm. This was due to only a small center portion of the lens being utilized by the camera’s sensor. But with full frame digital cameras equivalent to 35mm film becoming more prevalent and more affordable to the consumer, and an added renewed interest in street photography, the 50mm has regained some of its past glory. One can now use it to its full potential rather than as the poor man’s portrait lens on a cropped DSLR sensor.

Lemonade, shot with 50mm lens shot at f/8

The French photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson (1908-2004) did most of his work with a 50mm lens, whereas the American photographer Garry Winogrand (1928-1984) used a 28mm for a good part of his life. I spent some time thinking about each photographer’s very distinct preferences. I concluded that since Winogrand prowled the narrow sidewalks of New York City, he resorted (like many of his contemporaries) to a short focal length to get in everything that he was seeing in his field of view. A 50mm lens would be just too long to pull this off in a narrow working space of 4 to 10 feet. Plus, Winogrand liked to get in on the action. Bresson on the other hand was very stealth in his approach and liked to work from a distance–shoot and scram he called it! And like the painter he was, preferred the more flat, painterly look of the 50mm, This is due to the 50mm lens’ ability to compress objects and throw the background more out of focus than a short lens like the 28mm. Of course, all this is contingent on how small a lens aperture you are using combined with how close or far you are from your subject. Move far enough back, a longer lens can have a very large depth of field keeping much of the scene in focus, while even up close a short lens like a 28mm can throw the background out of focus, even creating a bit of bokeh.

Compare the previous images above. The 28mm shot of the kid blowing bubble gum was used at a wider aperture of f/5.6. The kids crossing the street was shot with a 35mm lens at f/8. And finally, the lemonade scene was shot with a 50mm lens at f/8. Notice how much flatter the 50mm is–more compressed with less separation between foreground and background objectors compared to the images taken with the 28mm and 35mm lenses. Even at f/8 the background shot with the 50mm is still slightly out of focus due in part that I was relatively close to the two people in the foreground. If got in that much closer to the people holding their drinks, the background would be just that more out of focus as I tried to keep that same couple in focus. The photo just below is a good example of how that would look. Even though the lemonade scene and the kid below were shot at f8 on the same lens, less of the scene is in focus with the kid due to my close proximity.

Spider-kid shot at f/8

And this is a scene shot with a 50mm from a distance. Even though I used an f-stop of 5.6, notice how much more of the scene is in focus by just stepping back.

Wider scene shot from a distance using 50mm

While photographers like Winogrand moved about on narrow city streets using shorter lenses to their advantage, Bresson traveled to parts of the world that at the time were less developed and therefore less congested. And when he was shooting in more developed urban environments, they were generally in Europe and Asia that had large public squares that allowed people to move about freely, and thus affording Bresson more distance between himself and his subject. Still, Bresson did use the 50mm as a closeup portrait lens when the need did arise. And unlike the complex distortion of a 28mm lens, the inherent compression of a 50mm used up close can be very flattering.

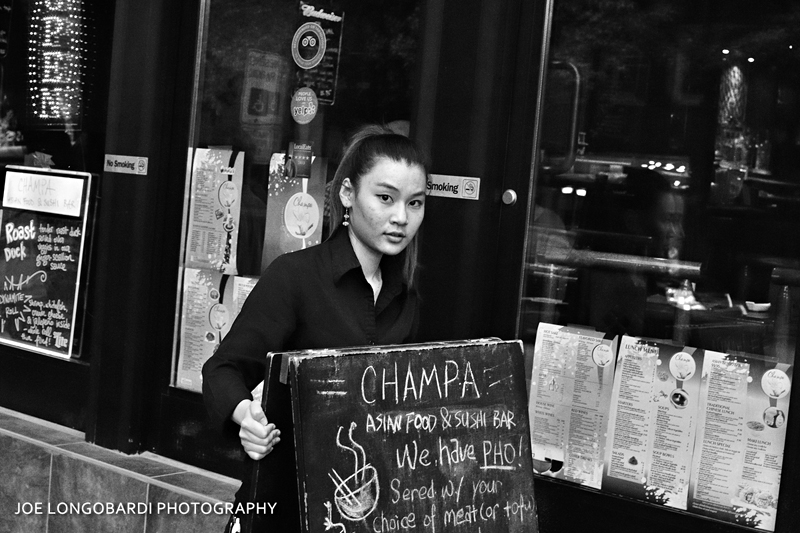

Street portrait with 50mm

Four young women, 50mm group portrait

Included in this blog are of images that I had taken in downtown Asheville using a 50mm lens on a full frame D700. Some were taken over a period of several weeks, while thers where shot in a time span of 30 minutes. The very idea that I can take in scenes up close or at a distance offer a very short period makes the 50mm a very versatile lens for most situations. I kept my eyes open for those moments between the moments happening up close and at a distance, avoiding the trap of capturing just any pedestrian traffic that was readily available. Because so much can be happening at once, I used the 50mm at it’s full potential by zooming in at narratives either at a distance or right in front of me. In these instances, the 50mm was neither too long nor too short to capture everything I found interesting. You could experiment with a longer lens like an 85mm or even 135mm, but it will keep you far removed from the action, plus you end up having either too little room to back up or you have to shoot from across the street to get more than just a face and shoulders.

Hopefully you have found this information helpful. This is a general outline of the basic principles of utilizing the 50mm. In all, the 50mm is a very versatile lens allowing the photographer to zoom in close enough while maintaining a comfortable distance from people in public. Yet, it is short enough to get close on tight, crowded sidewalks in a busy city. One other bit of advice: Challenge yourself–find that one one lens that calls out to you and use it exclusively for a month. After a series of hits and misses, things should fall into place as you begin to understand the limits and strengths of that particular lens. No one lens works for everyone. Street photography is about seeing, and needless to say, we all see the world differently!

Kid jumping, captured with 50mm

50mm used to photograph city sidewalk of downtown Asheville

I should add that I will be holding a street photography seminar on June 19, 2015 in downtown Asheville, North Carolina. It’s free and open to the public. The time is tentatively set for 5pm at the Vance Monument on Broadway and Biltmore. The intent is to offer advice via the facebook page and the actual meetup on the legalities of doing photography in a public location. We’ll also go over a few things such as copyrights and recent and past court rulings. We’ll go over the kind of lenses and cameras that work well for this genre of photography that includes the use of hyperfocusing and zone focusing to hip shooting. If you are interested, my advice is to bring along a camera and lens combination that can allow for full manual control. I will add updates on a Facebook events page on times and weather conditions as more details come together.

Hula Hoop in Pritchard Park

Light of a smoke

50mm up close and from the hip–not easy to do with a 50mm

All images © Joe Longobardi. All Rights Reserved.

Content © Joe Longobardi. All Rights Reserved. Powered by WordPress